In early fall of 2013, an export company in Botswana prepared a shipment of animal parts for Wayne LaPierre, the head of the National Rifle Association, and his wife, Susan. One of the business’s managers emailed the couple a list of trophies from their recent hunt and asked them to confirm its accuracy: one Cape-buffalo skull; two sheets of elephant skin; two elephant ears; four elephant tusks; and four front elephant feet. Once the inventory was confirmed, the email stated, “we will be able to start the dipping and packing process.” Ten days later, Susan wrote back with a request: The shipment should have no clear links to the LaPierres. She told the shipping company to use the name of an American taxidermist as “the consignee” for the items, and further requested that the company “not use our names anywhere if at all possible.” Susan noted that the couple also expected to receive, along with the elephant trophies, an assortment of skulls and skins from warthogs, impalas, a zebra, and a hyena. Once the animal parts arrived in the States, the taxidermist would turn them into decorations for the couple’s home in Virginia, and prepare the elephant skins so they could be used to make personal accessories, like handbags.

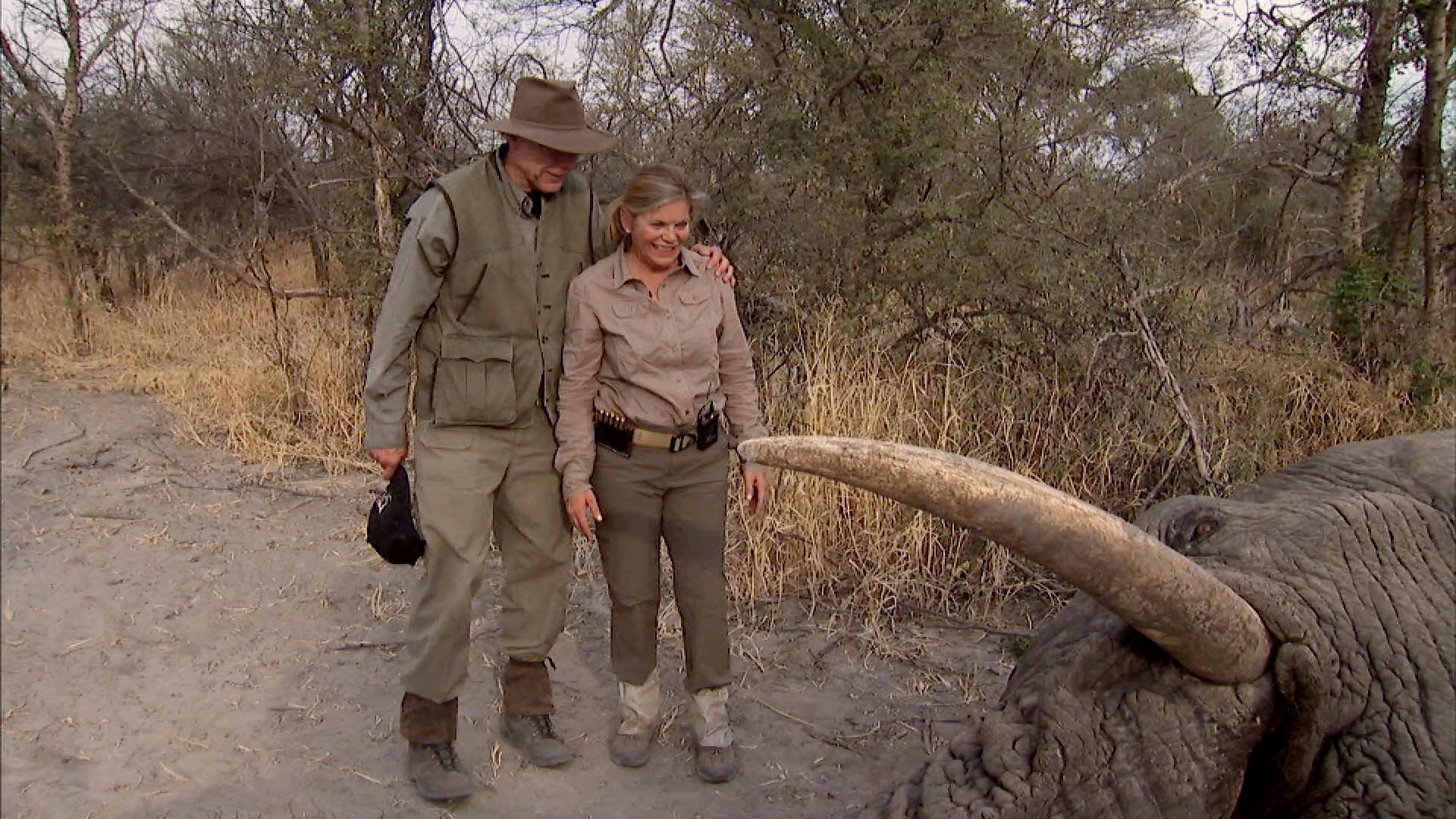

The LaPierres felt secrecy was needed, the emails show, because of a public uproar over an episode of the hunting show “Under Wild Skies,” in which the host, Tony Makris, had fatally shot an elephant. The NRA sponsored the program, and the couple feared potential blowback if the details of their Botswana hunt became public. Footage of their safari, which was filmed for “Under Wild Skies” and recently published by The Trace and The New Yorker, showed that Wayne had struggled to kill an elephant at close range, while Susan felled hers with a single shot and cut off its tail in jubilation. Plans to air an episode featuring the LaPierres’ hunt were cancelled.

Records obtained by The Trace and The New Yorker show that Susan leveraged the LaPierres’ status to secretly ship animal trophies from their safari to the United States, where the couple received free taxidermy work. New York Attorney General Letitia James, who has regulatory authority over the NRA, is currently seeking to dissolve the nonprofit for a range of alleged abuses, including a disregard for internal controls designed to prevent self-dealing and corruption by its executives. In a complaint filed last August, James’s office asserted that trophy fees and taxidermy work “constituted private benefits and gifts in excess of authorized amounts pursuant to NRA policy to LaPierre and his wife.” The new records appear to confirm those allegations. The NRA’s rules explicitly state that gifts from contractors cannot exceed $250. The shipping and taxidermy of the Botswana trophies cost thousands, and provided no benefit to the NRA — only to the LaPierres. In the complaint, James’s office alleged that the LaPierres also received improper benefits related to big-game hunting trips in countries including Tanzania, South Africa, and Argentina. The attorney general declined to comment further on the details of the case.

Taxidermy work orders containing the LaPierres’ names called for the elephants’ four front feet to be turned into “stools,” an “umbrella stand,” and a “trash can.” At their request, tusks were mounted, skulls were preserved, and the hyena became a rug. The episode represents a rare instance in which the gun group’s embattled chief executive is captured, on paper, unambiguously violating NRA rules; the emails show that Susan directed the process while Makris’s company, Under Wild Skies Inc., which received millions of dollars from the NRA, picked up the tab.

Andrew Arulanandam, the NRA’s managing director of public affairs, said, over email, that the LaPierres’ “activity in Botswana — from more than seven years ago — was legal and fully permitted.” The couple’s safari trips, he added, were meant to “extol the benefits of hunting and promote the brand of the NRA with one of its core audiences.” Moreover, he claimed, “Many of the most notable hunting trophies in question are at the NRA museum or have been donated by the NRA to other public attractions.”

The LaPierres’ effort to keep their taxidermy work secret spanned four months and involved multiple individuals, companies, and countries. On September 27, 2013, the shipping company in Botswana sent its first email to the LaPierres and informed them that the animal parts would be sent to a different company in Johannesburg before making their way to the United States. “We will be keeping you advised on the progress of this shipment as it moves along these processes,” the message said. In early October, after multiple phone calls with Susan, the American taxidermist wrote to one of the shipping agents involved in the exportation process. He explained that there had been a recent controversy involving Makris, and that the LaPierres “can not afford bad publicity and a out cry.” The taxidermist added, “That is why they are trying not to have there names show up on these shipments so the information does not fall into the wrong hands.” Two months later, the taxidermist checked in with Makris, and asked what he should do with the items once he received them. “W and Susan will tell you how they want theirs mounted,” Makris replied, before reminding the taxidermist that “they said you could handle the import discreetly.” Makris then informed the taxidermist that he would pick up the couple’s tab.

Throughout December 2013, emails show that the taxidermist negotiated with both export companies on the couple’s behalf, with Susan, as well as others, copied. “AS requested by the LaPierre’s in a earlier email there name and contact information is to be replaced with my name and contact information,” said one note to the Botswana company. The organization replied that trophies “can only be exported from Botswana in the name of the licensee,” and that “it’s been that way for years, and the export regulations stipulate this.” The taxidermist replied, “This request was only made by Susan and Wayne LaPierre and understand you need to follow the law were applicable.”

The taxidermist then turned his attention to the company in South Africa. On December 10, the taxidermist told Susan that, once the hunting trophies arrived in Johannesburg, an agent would generate a new airway bill to attach to the shipment, and enter the taxidermist’s name on it as the consignee instead of the LaPierres’. When the trophies arrived in the United States, and were cleared through government agencies, it would look as though they belonged to the taxidermist. “Awesome,” Susan replied.

Once the shipping crates landed in Johannesburg, another contact of the taxidermist’s drove two hours to check if the LaPierres’ names were written on the containers. When the friend discovered that they were, he scrubbed them off. In late January 2014, the taxidermist told Susan that the shipment had arrived. “Looks like everything is here and no protestors,” he wrote.

After Susan killed the elephant in Botswana, video shows, she was fixated on the creature’s feet. As she touched them, she said, “He’s so wrinkly… Wow. A podiatrist would love working on him.” Photographs of the taxidermied appendages show that the animal’s wrinkled, gray skin, the light coating of hair, and the massive, cracked toenails are all preserved, and, in the case of the stools, topped with wooden rings and black leather seating pads.

The taxidermist had successfully completed a highly sensitive, laborious project. Two years later, in 2016, he reached out to Susan because he was trying to buy a boat from someone she and Wayne knew, and he hoped Susan could connect them. In an email, the taxidermist said it was fine if she could not help, noting that “life will go on.” Still, he asked for the courtesy of a reply, one way or the other. He did not receive one.

Arulanandam, the NRA spokesperson, alleged that “communications” with the taxidermist stopped after he “appeared to make threats against members of an NRA delegation that participated in the Botswana excursion. He also sought benefits and payments to which he was not entitled.”

The taxidermist wrote a parting email three months later expressing his frustration at the lack of response. It wasn’t so long ago, he said, that Susan had “begged” him over the phone to remove the LaPierres’ names from their “harvested Elephants,” and promised him “ ‘A BIG FAVOR’ ” in return. In case she had forgotten, he reminded her, “you could not afford protesters” and a “media shit storm.”